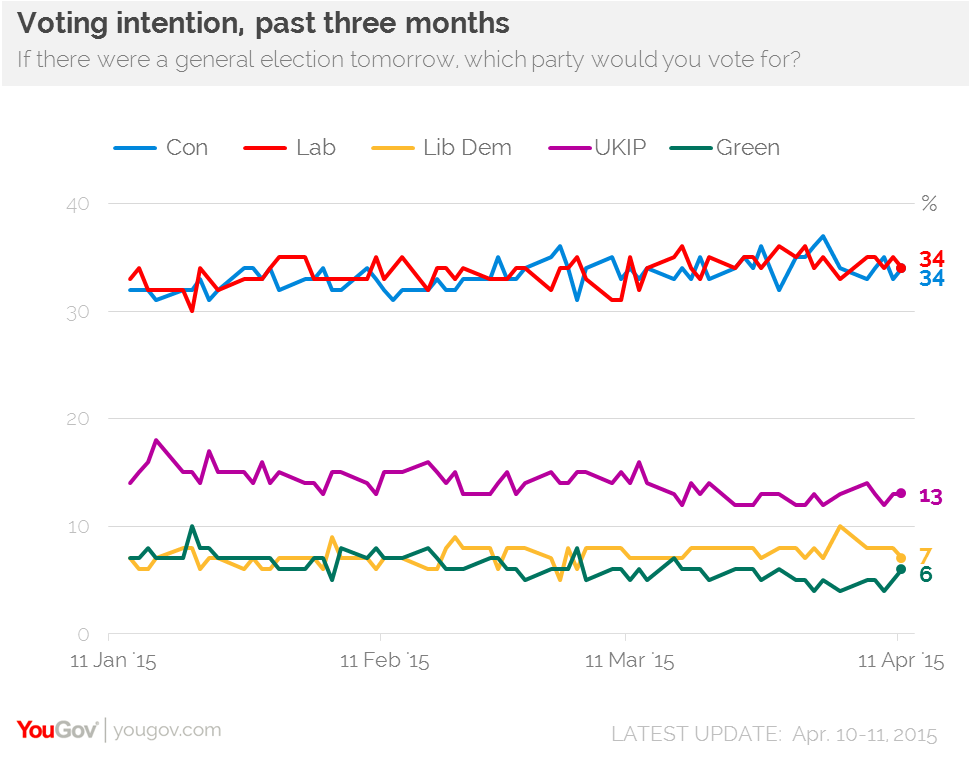

The last few months of electioneering have been disappointing for political hacks. Ahead of the national poll on May 7th the parties endured a steady stalemate. Labour and the Tories tussle over a third of the popular vote apiece, whilst the Liberal Democrats, Greens and Ukip fight over the remnants, their shares fairly constant.

As Private Eye has pointed out, this has led to any number of headlines from Fleet Street proclaiming how unpredictable this election is. When translated into seats Labour and the Tories have been on target to collect 280 each, whilst the Lib Dems are reduced to around 25 and the Greens and Ukip pick up a handful between them.

Far north of Westminster the Scottish National Party (SNP) has flourished since it failed to secure the country’s independence in the referendum last September. It is now on course to trounce Labour and the Lib Dems in May throughout Scotland, increasing its MPs from six in 2010 to between 40 and more than 50, depending on who you ask.

Political polls always contain a margin of error that tends not to make it in the papers’ reports (three to four percent per party, according to YouGov’s Peter Kellner), but this time round the uncertainty has dominated coverage. The key question is whether Tories or Labour will have the 326 seats necessary to secure a majority (or 323 in practice, given Sinn Fein’s five MPs refuse to sit in the Commons).

But even if the swing towards the fringes has made this general election more interesting, it has not made it quite as unpredictable as advertised. Most papers have been predicting a hung parliament for some time, and that is almost certainly what we will get. What is harder to charter is how negotiations will pan out between the contenders, but there are some things we can safely say.

First, the SNP will not work with the Tories. As early as August its leader Nicola Sturgeon told a party’s annual conference that: “The SNP will never put the Tories into government.” She has also said she would consider working with Labour, whose leader Ed Miliband has ruled out a coalition but not a looser deal.

Combined with Lib Dem support this gives Miliband a better hand than his Tory counterpart. Whilst incumbent prime minister David Cameron could potentially reform the Condem coalition he might have to rope in support from Northern Ireland to inch a majority, which in turn would be highly unstable.

Because of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act even if no party can govern effectively the parliament will stagger on unless two-thirds of the house vote to dissolve it. Though this is a more democratic method of scheduling elections (previously the prerogative of the prime minister), if more than a third of MPs stand risk losing their seat they are unlikely to vote for early dissolution, even in a zombie parliament.

Just such a parliament is a likely outcome after May. Though the Right Dishonourable predicted this could lead to a constitutional crisis, it is in the British character not to make a fuss. Without the fixed-terms a minority or weak coalition might have governed for a short time before returning to the polls, but with it Westminster could stand impotent for years.

Hey, if it’s good enough for US Congress…