As the strife in Labour mounted following the EU referendum, its former leader Neil Kinnock told a meeting of the party’s MPs: “Dammit this is our party! I’ve been in it for 60 years! I’m not leaving it to anybody!”

The sentiment was repeated, albeit in milder form, by the former leadership hopeful Liz Kendall in an interview with GQ last week.

“I’m not going to leave my party,” she said. “I am not going to give up my party to people who do not represent what we believe.”

Who exactly the “we” or the “our” Kinnock and Kendall refer to is unclear in the above statements.

Indeed, the tussle over Britain’s major leftwing party has revealed a complex ownership that underpins any large organisation.

Labour has tiers of membership. At its base is the general membership and associates, made up of those paying full membership fees, those on a discount, and trade unionists.

Above that you have the party chiefs, those with official activists roles, and those even being paid for various duties within the party.

And separate to both these groups are the Labour MPs and councillors, voted in by the British electorate and paid by the state.

All these groups can plausibly claim to be Labour in some form.

Labour must somewhat be its general membership, but those people have less of a say in how things are run than the organisers, and both those groups probably have less influence on the outside world than the elected politicians.

The tension between these groups has underpinned Labour history since before the party’s formation. Even in the early years the likes of Ramsay MacDonald were managing the more radical socialist tendencies of the Independent Labour Party, which eventually split from the main pack.

The first century of Labour history pivots around the tussle between the centrists seeking to accommodate the electorate and the radicals pushing for a purer socialist agenda.

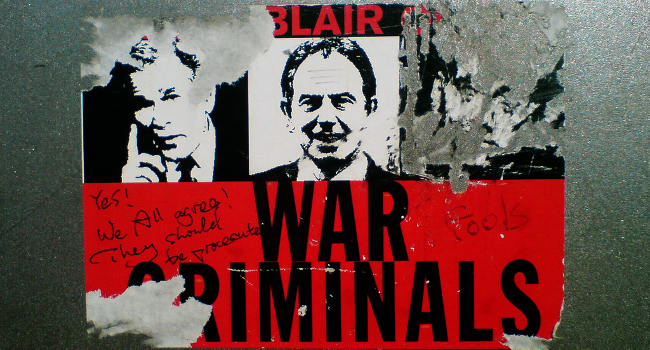

When Tony Blair – he of Iraq War infamy who occasionally won general elections – rewrote Clause IV in 1995 to take out the bits about “common ownership of the means of production” it appeared as though the centrists had finally won.

And it is this centrist or moderate tendency in Labour that Kendall and Kinnock talk about when they describe “our party”.

But the reality is that Labour, at least internally, is now firmly the party of its new leader Jeremy Corbyn, who will surely be re-elected this autumn, as well as his shadow chancellor John McDonnell and the campaigning group Momentum.

Not only do these Corbynites command a majority of support from party members, but they have also strengthened their position on the National Executive Committee (NEC) and are reportedly plotting deselection of non-compliant MPs.

When Kendall says she will not “give up my party to people who do not represent what we believe”, this is a contradiction. It is because Labour members now believe different things from Kendall that Corbyn’s cohort was able to take control.

This was what made the attempts to exclude Corbyn from the latest leadership contest so futile. Even if he had been excluded, what sort of victory would it have been for MPs and the NEC to openly subvert the wishes of the members?

Kendall and Kinnock should accept that whatever Labour was or could have been it is now firmly Corbynite. And whatever appeals to electability or pragmatism the centrists come up with, that is unlikely to change.

At least for Kinnock there will be some consolation. He isn’t leaving the party to anybody. The party left him.

Image Credit – War Criminals, April 2007 by Fabio Venni