For no party has the General Election been sadder than for the Liberal Democrats. Their crumbling from 56 to 8 seats (which may be reduced to 7 if Scottish MP Alistair Carmichael calls a byelection) was perhaps the defining factor in lifting the Tories over the majority threshold in the Commons.

For their pains as the junior half of the coalition the Liberals have been traduced by both sides. Likely knowing their protest vote would vanish and others would abandon them to the fringe Left, the Tories flooded Liberal marginals with cash. The result was the worst drubbing since the Social Democratic Party teamed up with Gladstone’s descendent in the 80s.

In the wake of the collapse the Tories are lining up illiberal bills they could never have got through with the Liberals in tow. One bans legal highs (the Psychoactive Substances Bill). Another launches a censorship scheme (the Extremism Bill). Yet another will authorise more government snooping (the Investigatory Powers Bill).

But perhaps most troubling, and most baffling, is the furore over the Human Rights Act, a 1998 bill that the Tories promised to scrap in what prime minister David Cameron’s press officer claims is a move to make Britain’s Supreme Court “the ultimate arbiter of human rights”. As The Right Dishonourable has argued before, the plan is a mess.

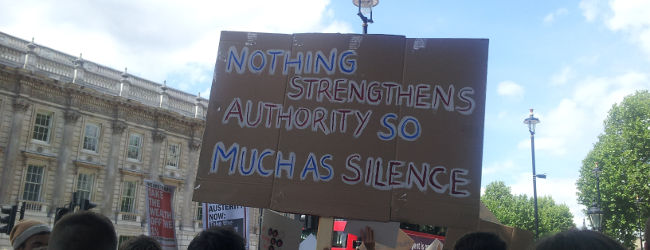

It was this piece of legislation that motivated fragments of the Left to gather near Parliament Square last Saturday. Whilst mostly these were Liberals there was a smattering of the Socialist Worker’s Party (which appears to have set up a permanent gazebo across from Downing Street) and a few odds and sods.

Such rallies these days show in microcosm why the Left was so roundly beaten. Many of its supporters remain bitter that the Liberals ever went into coalition with the hated Conservatives. One bystander even heckled the “Yellow Tories” as a pack of placard-carrying Liberals walked away from the protest, which congregated opposite Downing Street.

That another protest levelled against austerity was taking place at around the same time on Westminster Bridge, not three minutes walk from Downing Street, says much of the split ambitions of the Left these days too. Liberalism and socialism may not be incompatible, but they need not be allies either.

As the views of journalist Owen Jones readily attest, whoever wins the contest for leadership of the Labour party is unlikely to satisfy those who turn out to anti-austerity marches. Much as there is a portion of the Tories who will not accept globalisation, there are those within the Left that rebel against its uglier effects: pollution, deprivation and exploitation. Such people will not savour a return to Blairism.

At least on this front the Liberals do not seem so divided. Tim Farron, the MP and grassroots’ favourite, has been much in view at the post-election meetings, shaking hands and making speeches as he prepares for a leadership bid. Whether he or his fellow MP Norman Lamb wins the ensuing contest, there are not enough Liberals for a major rupture to be anything other than suicide.

That difference aside, both Liberal and Labour will have a challenge to reëstablish what it means to be in opposition, and more broadly what it means to be on the Left. Both have what the corporate world terms a “branding issue”. For Labour this means harnessing some of the breadth that Tony Blair mustered in his hat-trick of victories – a task that may prove impossible for now.

For the Liberals, however, it means adapting to the fractured multi-party state they helped build. It means fewer protest votes. And as Saturday showed, it means greater competition from other leftwing political voices, most obviously in Scotland from the Scottish National Party.

The Left has five years until the next general election. Whether this is enough time remains to be seen.

Header Image – Human Rights Act Protest, May 30th 2015 by The Right Dishonourable